That is a big statement to make, so can tyre and polymer pyrolysis really be the future? This article looks at the subject and tries to find some answers.

As we have written many times, pyrolysis is not a new business, it has been around since the iron age, used to make charcoal that enabled the production of iron and steel.

Today, it still gets used to make charcoal, both industrially and in small batch rural business applications. However, we are looking at tyre and polymer pyrolysis (plastics to the public). Here, the development of suitable pyrolysis plants has been a long-term project, for some, a lifetime project. So why, suddenly, has the prospect of tyre and polymer pyrolysis changed so dramatically as it has in the past three years?

There have to be three sides to every business development – there has to be a demand, there has to be a feedstock, and there has to be the required investment. If any one of these three is missing, then the project cannot take place. Of course the technology to enable the operation is a given here.

In the case of tyres and polymers, there is ample evidence that the feedstock exists. The news is constantly full of stories about waste plastics on beaches, rivers and in the oceans. We clearly have a plastic problem that needs dealing with.

Tyres are perhaps less obvious to the general public unless they happen to have had a tyre dump on their doorstep. Tyres tend to be collected and either processed in some way or, in some markets, stockpiled or landfilled still. They do not have the same visual impact as plastics, so tyres remain at the end of life, as ignored by the public as they are in their daily use.

However, the world produces around 380 million tonnes of plastics every year (Source:Earthday) and that does not include textiles that are also polymers made from the same materials, and 2.7 billion units of tyres in 2022, according to Smithers – that does not include conveyor belts, rubber sheeting or other uses for rubber. In the case of both, it can be presumed that once manufactured, they will have a finite lifespan and then need recycling – though at the moment, much of both get discarded, especially in developing nations and some developed nations.

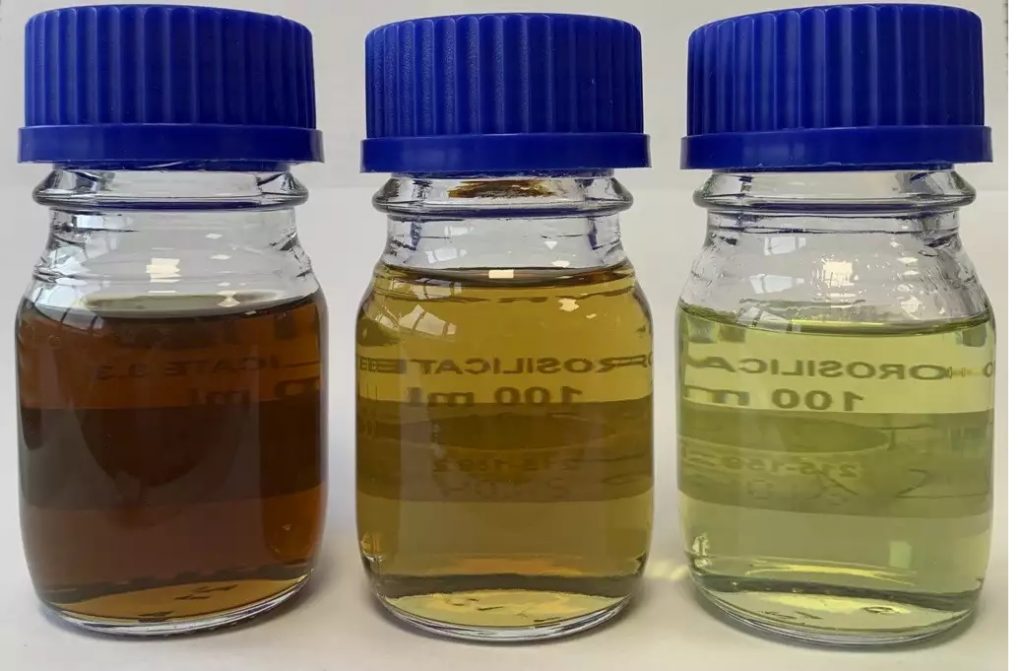

Tyres and plastics have one other thing in common; they need oil to manufacture them. Oil is one of the main outputs of the pyrolysis of tyres and plastics. The process takes the end-of-life product and returns it to where much of it came from – it becomes, in part, oil again, along with carbonaceous char and in the case of tyres, some steel.

So, it is clear that the feedstock for the pyrolysis sector exists or should exist. We will return to that point.

So, what about the demand?

Here is where the market for pyrolysis has changed. Some 10 years ago, one pyrolysis pilot project went to an oil company with the results of their research and the oil company was impressed by the outputs – in oil terms, not so much the recovered carbon black element. However, the oil company advised that they would only be interested in tyre pyrolysis if the project could be scaled up to around 50,000 tonnes per annum, as a minimum. For the pyrolysis sector, this volume was a barrier. How do you go from a pilot plant to 50,000 tonnes a year when there is no existing market? That for decades, had been the barrier to the development of the tyre pyrolysis market.

The tyre industry uses upwards of 8.5 million tonnes of virgin carbon black every year, every car tyre uses around 3kg of carbon black, or around 22 per cent of its weight is carbon black.

Currently, that all comes from crude oil, or methane, or in some cases, acetylene. That is a huge market – the tyre industry consumes up to 88 per cent of the virgin carbon black produced each year. That figure varies depending on which report we look at, but for this purpose, we will be optimistic and take this high figure. That market is worth somewhere around $15 billion each year and rising, according to Fortune Business Insights.

Carbon black can be recovered through pyrolysis, though the initial output is not always a direct substitute for virgin carbon black. The global replacement market using recovered carbon black in tyres is standing at around one per cent across the industry. One per cent does not seem like a lot, but one per cent of $15 billion is still $150 million in value. This is just the starting point.

However, that value is rising. Leading tyre companies have started elevating their use of recovered carbon black and tyre pyrolysis oil-derived carbon black. The level of interest in recovered carbon black is such that Michelin has invested in Scandinavian Enviro Systems, and has bought the technology rights for plants for its own use – the first of these is being established in Chile. Michelin and Bridgestone also came together to announce a joint project to create a market framework for recovered carbon black – this was a real change of direction, instead of the pyrolysis operators going to the tyre manufacturers with what they produced, Michelin and Bridgestone went to the pyrolysis sector and said this is what we need in terms of specification and volumes. Continental is working with German pyrolysis firm Pyrum Innovations, and in South Korea LD Carbon is now supplying Sumitomo Rubber Industries. In the USA, Delta and Bolder are again supplying the American tyre makers and the plastics industries. The list of companies with active projects to upscale production is increasing and this is largely due to the notification from the tyre industry that it is now willing and ready to buy recovered carbon black. Without that demand, there would be little or no movement in the market.

So, we have a feedstock, we have a demand. What about the investment?

Here we have a Curate’s Egg of a scenario, it is good in parts. Companies such as Bolder, Enviro, Pyrum, Circtec and a few others have managed to secure the investment and are forging ahead with plans to develop upscaled projects. Most are looking at 40-50,000 tonne plants, Pyrum is looking at multiple 20,000 tonne plants, and has several projects lined up for construction in the coming years.

Others are finding raising the capital investment a bit more challenging, and one of the issues is feedstock. So, we come full circle in the discussion.

Why is feedstock an issue?

The tyre recovery rate in Europe, for example, is shown as being high, in the 90 – 100 per cent level, according to the ETRMA. However, an analysis of where those tyres go is revealing; half of the tyres, and this has been pretty consistent for the past decade, go to tyre-derived fuel, largely for cement kilns in Europe and North Africa. The other half gets processed to rubber crumb and chip for various uses, the largest of which is sports surfaces – both bonded and crumb rubber infill.

However, there are reports from recyclers that they cannot acquire sufficient material to meet contracts in the UK. This shortage impacts both the sports surfacing and the TDF sector.

The reason is that the market has been undermined by the export sector shipping tyres to largely India. It is cheaper to cut and bale tyres than it is to shred or crumb them, so the predominant market sector in the UK is currently for export, with upwards of 350,000 tonnes per annum being exported. There is anecdotal evidence that exports to India from other European states are also increasing.

This creates a market scenario where there is demand, but the feedstock is in question. In the UK, we are aware of the inability of recyclers to meet 50,000-ton TDF contracts already. This bottleneck in the feedstock supply has a knock-on impact on the projected recycling plants seeking investment.

With no guaranteed feedstock, there is a reduced prospect of attracting investors. Without the investors, the development of the plant becomes problematic. The feedstock issue needs to be addressed before there can be any large-scale development of the UK pyrolysis market – at least.

No cloud without a silver lining

So, why, then is pyrolysis the future of tyre and polymer recycling? For plastics, the answer is simple, we produce 380 million metric tons of plastic that eventually reaches end-of-life and will need to be recycled rather than dumped. Plastics can often be recycled as plastics, but there is an entropy in quality and performance with every cycle, and the consumer is not a big fan, yet, of recycled plastics. Thus, if a terminal solution is required for plastics, pyrolysis is the only real, potentially high-volume route to relieving the plastics waste problem. Plastics go back, largely to oil from whence they came – with the potential to also produce hydrogen in the process – and hydrogen is going to be in big demand in the future. It may surpass the demand for pyrolysis oils.

For tyres, the future of pyrolysis is already clear as tyre manufacturers plan to ramp up the use of recovered carbon black – the market will grow immensely if the tyre sector uses just another one percent of recovered carbon black, that $150 million becomes $300 million very quickly. If the target of 10 per cent recovered carbon black is achieved, then the market becomes $1.5 billion per annum. That is with the market for tyres stagnant. However, the tyre market is growing and the future size of the market for recovered carbon black will be much greater than it is today.

We will need recycling methods that have a minimal environmental impact, pyrolysis carried out to the highest standards is potentially one of the best end solutions for tyre and polymer processing. Some might argue that it will need to be aligned with carbon capture schemes, but that is a challenge for the future.

But what about the feedstock?

The European Commission keeps coming around to review crumb rubber infill. It has repeatedly reduced the permissible PAH content; it can consider other potential risks from leachates, and it has crumb rubber infill in its sights as a microplastic. It is seeking the guidance of the ECHA RAC on the PAH, again. According to the EuRIC mechanical tyre recycling board, any ban on crumb rubber could put 400,000 tons of tyres into the waste stream with nowhere to go. That would resolve the feedstock issues for tyre pyrolysis plants.

Of course, it isn’t quite as simple as it seems, but in terms of the available technologies for recycling waste plastics and rubbers, at the end of a chain of circularity (should that not be spirality?) tyre and polymer pyrolysis is our currently available best option to recover materials from end of life tyres and plastics.

There are still stakeholder challenges to be addressed for any pyrolysis project, but that is a whole different discussion.