Rubberised asphalt has long been a target for recycled materials, rubber and polymers being used to improve performance is a long-standing technology

The use of rubber as a bitumen modifier is not a new technology, though there are new technologies around the concept, such as Recykl’s Smapol bitumen modifier that includes textile fibres to improve the strength of the asphalt.

Adding rubber, creates greater flexibility to asphalt, it helps it absorb impacts, and it minimises damage from extremes of weather, making the asphalt frost resistant, which is where most of the cracking damage comes from.

Bitumen recipes vary from supplier to supplier, from state to state, but the norm is for rubber powder to be added to the bitumen – either at the mixing plant, or at the site.

A 10cm thick layer of asphalt, on twin 3.5 metre lanes would require around 700m3 per kilometre (Aggregate Industries calculator). With bitumen at 5% of the asphalt mix, that equates to 35 cubic metres of bitumen per kilometre. The highest percentage of rubber in bitumen for asphalt use is 15 per cent, probably usually closer to five per cent according to Resource Responsible Use of Recycled Tire Rubber in Asphalt Pavements.

5 per cent of 35 cubic metres is 1.75 cubic metres of rubber (which may not all be from tyres) per kilometre.

An end of life truck tyre may weight around 60kg, that is about mid range, it will contain around 7.5kg of steel, leaving 52.5 kg rubber when processed.

There is around 500 kg of rubber in a cubic metre, so roughly 16 end of life truck tyres per Kilometre.

The Tarmac proportions

Brian Kent at Tarmac advised that their two products, – Rubber Modified SMA at 0.67% rubber which would be 1 car tyre per tonne, and UltiPave R at 1% rubber which would be 1.5 car tyres per tonne.

Tarmac’s figures are somewhat more positive than those extrapolated from the US document, suggesting; Rubber Modified SMA would be 500 tyres per km at 40mm depth for one 1km lane at 3.7m width, UltiPave R would be 750 tyres.

For clarity, Tarmac use about 10kg of rubber /tonne in RMA and 15kg/tonne in UltiPave R.

Volumes in use

According to the UK government, £8.3 billion of redirected HS2 funding is enough to resurface over 5,000 miles of road. So, if, those 5000 miles of road resurfacing were to be carried out using Tarmacs UltiPave R, that would be 8046.72km, call it 8050km. that road resurfaces at 40mm, would utilise rubber from 6,037,500 car tyres. That, in itself might face a feedstock issue. With the average waste car tyre weighing around 11 kilos, that would require 66,412 tons of powderised car tyre rubber. There are few recyclers in the UK who have the capability to produce powderised rubber, and investment in equipment to create the material is undermined two-fold. Firstly, by the ease of export compared to the cost of processing, and secondly, by the lack of any mandate encouraging the use of rubberised asphalt.

One asphalt specialist told the ETRA conference that rubberised asphalt was not a solution, there were only four tyres per ton of asphalt. There are clearly differences in the technologies and construction methods used.

Rubberised asphalt is too good

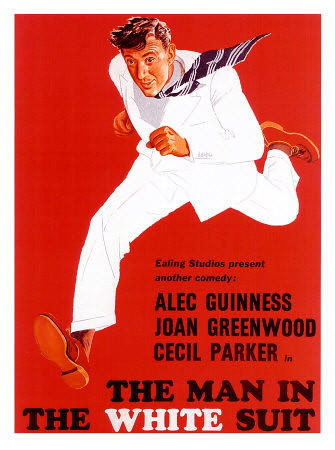

However, he did argue that the real problem with rubberised asphalt was that it was too good. It outlasted conventional asphalt by many times. This, he argued, gave contractors pause for thought. It was great if they won the tender for the work, but if they laid a road that would last for 25 years, where would the next contract come from? This is the Man in a White Suit Syndrome.

In the 1951 film starring Alec Guinness, he played a textile researcher who developed a material that never got dirty and would never wear out. He believed that this would solve many of the world’s clothing problems, no need to keep changing clothes, no need for laborious laundry. It was a solution that would make life better for everyone – except, of course, the mill owners would find themselves struggling for contracts, the workers would eventually lose their jobs, and it would impact negatively on all associated industries. In 1951 there was no consideration as to how this material would be recycled. Of course, despite the fact that this was the perfect textile, it was buried by the industry because it would put them out of business.

This is exactly the challenge faced by the proponents of rubberised asphalt. It is too good to use.

The everlasting bridge

Serji Amerkhanian referred to this when Tyre and Rubber Recycling interviewed him about rubberised asphalt. “I was approached about a bridge that needed repaired every year. I told them, I have a solution,” he said. “I was contracted to resurface the road across the bridge with rubberised asphalt. I said call me when it needs repaired. I didn’t get a call. They didn’t need to repair the bridge again.

“How many more kilometres of rubberised asphalt have been used in that country? None. The contractors fear that they will put themselves out of work.”

Costis Keridis from Greece spoke about the challenges that the rubberised asphalt sector faced, and one was the myth that the mixture cannot be changed – it has worked for us for decades, why would we change it? Why would they change it for something that would put them out of business? This is an argument made by many in the rubber industry that is creating a barrier to the use of recycled materials, but that is another story to be written.

In the context of rubberised asphalt, the Man in the White Suit is an apt comparison. In the movie, the Alex Guinness character, Stratton, runs through the streets pursued by factory workers and mill owners alike. Under stress, his “perfect suit” fails, but when revisiting his notes, he sees his error and sets out to improve the material. The analogy with rubberised asphalt development is clear, if unintended.